Robert John Lesney

Fiction Story

Cobbler, cobbler, mend my shoe.

Get it done by half-past two.

Half-past two is much too late, get it done by half past eight.

Cobbler, cobbler, mend my boot.

Mend it well to fit my foot.

Stitch it up and stitch it down, and I’ll give you half a crown.

English nursery rhyme.

In those days, English nursery rhymes were taught in primary schools to make English an enjoyable subject to study. Singing class was always a happy session for children. Little Tee learned many nursery rhymes by heart, and like the other children sang them joyfully. Except for one – the one about a cobbler. He knew what the song was about, and what it meant. No child of a tradesman liked to sing a song that mocked his father’s profession.

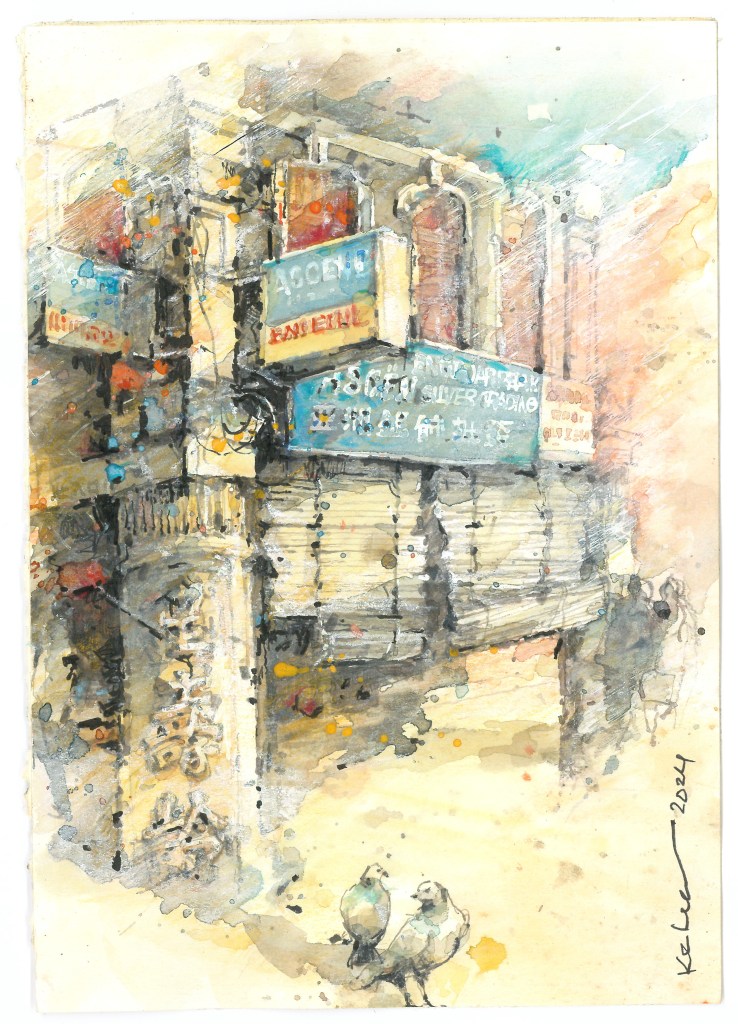

Tee’s father was a cobbler in Chinatown. Besides repairing old shoes, he made and sold wooden clogs, a common type of footwear worn in wet kitchens and dirty back lanes in the old days. The sale of clogs was usually brisk during the wet season. Impatient customers often wanted his father to rush his work and they often haggled over the price. But a good cobbler would always take his work seriously, and would never do a fast and shoddy job.

“Patience is a craftsman’s companion,” his father always said.

Tee’s father, Ah Teck began learning his craft during the war years. Ah Teck was born to poor parents who could not afford to send him to school. Instead, he worked as an apprentice to an old shoemaker in a small country town.

One day a soldier brought a pair of combat boots to him for repair. He worked fast – stitched, mended, and polished them until they looked new. But the soldier never returned to collect his boots or pay for the work done. So, he proudly displayed this pair of shiny black boots at the shop front for passers-by to view his handiwork.

After he got married, Ah Teck and his wife left for Kuala Lumpur. He wanted his children to have a good education in the city so that they could become successful in life, and not be an illiterate like himself. He set up a small cobbler shop in Petaling Street. He worked long hours and saved every cent he earned.

Soon he was able to send Tee to a mission school in the Chinatown neighbourhood. When school was over, Tee would help his father with light chores at his workshop. He could do a good polishing job and make old shoes shine like new again. At closing time, he threw out trash, and carefully packed up the tools in a tool box. There had been times when a tiny tool got missing or misplaced, and his father would get angry. But only for a moment, for deep in his heart he really appreciated all the little help his eight years old son could offer him.

The monsoon season arrived one year bringing heavy rain to the city for many days. As a result, many houses in low-lying areas were flooded. Temporary shelters were set up for flood victims in schools and community halls. Several stranded families took refuge in Tee’s school. During school assembly, the headmaster highlighted the plight of the flood victims and appealed for donations of cash or kind. On hearing that, Tee decided to help.

“How can I help these poor people?” Tee wondered. “What can I give?”

Back home, Tee asked his parents.

“We are also poor,” Ah Teck said. “I don’t have any money to give.”

Then Tee’s younger sister suggested giving away their new clogs. “We have unused ones in the kitchen,” she said excitedly.

With sympathetic eyes, Tee’s mother agreed, “We should give what we can spare.”

But Tee’s father remained silent. He was aware of some old Chinese beliefs and customs. Things like not washing hair on a festive day, and not wearing black to a wedding. Many Chinese of his generation disapproved of footwear as a gift. He had seen the practice of ‘villain-hitting’ where a temple medium would burn incense and chant prayers while beating an image of a person loudly with a shoe or a clog. This was done to help someone curse an enemy or to ward off evil spirits. Hence, the receiving of footwear as a gift was looked upon as inviting bad luck to oneself. Similarly, the gift of a clock was considered improper as it may indicate an untimely death to a receiver. Such were some superstitious beliefs among Chinese people in conservative times.

With such thoughts going on in his mind, Tee’s father turned to his wife and said, “Let’s give something else.”

However, Tee and his sister insisted that they give something their father had made specially for them. Their mother seemed to agree.

The next morning, Tee arrived at school with two pairs of new clogs in a paper bag. They were the trendy peanut-shaped children’s clogs with plastic foot straps in blue and pink. It certainly cost more than the ordinary plain-looking clogs with rubber straps. When the last lesson for the day was over, Tee headed to the school hall immediately. He was elated that he had something to donate to the flood victims.

The headmaster who was there overseeing relief distribution saw Tee and greeted him.

“Ahh…Tee, the cobbler’s son, what have you brought?”

“Sir, these are clogs made by my father. We want to give them away to the poor people,” Tee said proudly.

The headmaster opened the bag and gave a chirpy smile. “Ahh…wooden clogs! Very useful during this rainy season. Do say thank you to your dad for me.”

Inside the hall, Red Cross volunteers were distributing items collected from the public: blankets, packets of noodles and canned food. With Tee by his side, the headmaster approached some Chinese families with children. He held up the clogs and asked if they would like to have them for their little ones. But all of them shook their heads instantly.

Tee was disappointed indeed. He wanted to leave instantly. What would his parents and sister think when he took home the unwanted clogs? His father would feel insulted, or even angry!

Noticing Tee’s teary eyes, the headmaster took him aside. He praised Tee for his act of charity and suggested that he stay a little while longer to help him with tea preparation. Tee decided to stay on and help.

Meanwhile, the sky had turned dark and rain started again. Just then a truckload of people arrived. This was a group of squatters, elderly people and children, whose homes were lost in a landslide. They were all drenched. An old man walked slowly towards the headmaster to thank him for giving his people shelter for the night. They had lost everything.

The headmaster ushered them into the hall where aid volunteers quickly came around to help. Suddenly, Tee recognised a boy among this group of homeless people and called out to him.

“Hey Arvin! What happened to you, my friend?”

Arvin had once been a classmate of Tee. Often during recess time, the two boys would sit together in the shade of a flame tree and chat, or share a quick snack. Unfortunately, Arvin had had to drop out of school after his father died in an accident. The headmaster also remembered Arvin, the son of a rubber tapper. On noticing that he was barefoot, the headmaster said;[1]

“Arvin, would you like a pair of clogs to wear?”

“Yes Sir,” replied Arvin enthusiastically. “Can I have another pair for my sister?”

“Yes, of course,” said the headmaster. He took the clogs out of the paper bag and exclaimed, “Here’s a pink pair for your sister. These clogs were made by Tee’s father!”

Seeing those beautiful handmade clogs, Arvin could only utter a soft, “Thank you, Tee.”

Brimming with joy, Tee put his arm around Arvin and said, “I’m happy you like them, my friend.”

The headmaster turned to Tee with a knowing smile and remarked, “Always remember that a friend in need is a friend indeed.” Then the two of them went into the pantry to bring more tea and biscuits to the weary crowd in the school hall.

Rain continued to pour that night. Snug in a warm bed in a tiny room above a cobbler’s shop in Chinatown, a little boy slept soundly, proud that his father, a simple cobbler skilled at repairing shoes and making wooden clogs, had played a part in giving some kind of help to others in dire need.

About the author

Robert J Lesney was born and bred in Kuala Lumpur. A true-blue KLite, as long time residents of the city would like to be called, he has published in 2019 a travelogue I Love KL which features some fascinating places to visit in KL. A former ESL teacher of over thirty years, Lesney now spends his retirement years pursuing things of interests: travelling, watching old movies and listening to old songs. When in the mood, a little painting, or a little writing. Occasionally, he’d put on a tour guide’s cap and take visitors ‘jalan-jalan’ in his beloved hometown KL.

HELP US ADVANCE THE CONVERSATION & GROW THIS PROJECT

Project Future Malaysia wants to create conditions to guide an expansive vision of the future for Malaysia. This perspective will include a deeper engagement with science, technology and the various arts of literature, philosophy, film and music. By re-imagining and manifesting better alternatives for Malaysia’s future, we are freed from our everyday assumptions about what is possible. We can then imagine pathways forward which enable us to embrace bolder visions and hopeful possibilities for Malaysia’s future. If you resonate with the vision of this project, we invite you to grow and support this project via collaborations and conversations.

As a not-for-profit venture, we welcome values-aligned funders, partners and collaborators including suggestions of programming, improvements or corrections on this website and project.

COPYRIGHT

Copyright of artworks and text remain with their copyright owners. Please reference Project Future Malaysia and the copyright owner(s) if you are using any images or information from this website.